Unlocking the Connection: How Jaw, Breathing, Posture, and the Hyoid Bone Interact

Introduction: It’s All Connected (No, Really)

What do mouth breathing, poor posture, teeth grinding at night, and waking up feeling like your throat’s been in a wrestling match all have in common? Surprisingly, a little horseshoe-shaped bone in your throat called the hyoid.

This essay unpacks the complex and often overlooked connections between jaw mechanics, breathing patterns, postural alignment, and the hyoid bone—a muscular keystone at the intersection of function and dysfunction. Whether you’re dealing with sleep disturbances, jaw pain, tension headaches, or just curious about how something as simple as swallowing could affect your shoulder tension, you’re in the right place.

Let’s break down how your body’s upper corridor—jaw, neck, throat, airway, and cranium—operates as one highly coordinated system. We’ll examine the anatomy, functional roles, signs of dysfunction, and most importantly, how movement and manual therapy can help bring things back into sync.

Anatomy and Functional Biomechanics

Meet the Hyoid: The Floating Bone with a Big Job

The hyoid bone is unique. It’s the only bone in the human body that doesn’t directly articulate with any other bone—it’s suspended in your throat like a swing between muscle attachments. Located just above the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple), the hyoid serves as an anchor point for eight key muscles responsible for vital tasks like breathing, swallowing, speaking, and maintaining airway tone.

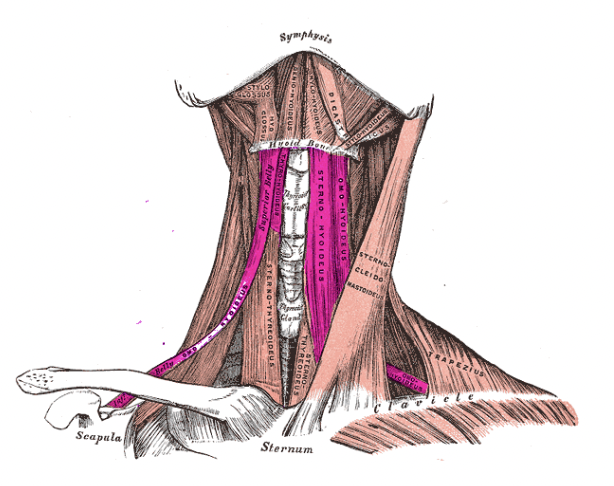

Two main groups of muscles are involved:

Suprahyoid muscles: These sit above the hyoid and include the digastric (anterior and posterior bellies), mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and stylohyoid. Their primary job is to lift the hyoid during swallowing or lower the mandible when the hyoid is fixed (Park et al., 2015).

Infrahyoid muscles: These run below the hyoid and include the sternohyoid, omohyoid, thyrohyoid, and sternothyroid. They help depress the hyoid and larynx during swallowing and phonation, while stabilising airway structures (Yoo et al., 2020).

Together, these muscles function like guy wires on a suspension bridge

—balancing tension to allow controlled motion between the jaw, throat, and chest.

The Jaw-Hyoid Connection

The jaw and hyoid are linked both mechanically and neurologically. When you swallow, your jaw briefly stabilises, your tongue presses against the palate, and the hyoid elevates to guide food or saliva past the airway and into the oesophagus.

But when dysfunction occurs—say from chronic mouth breathing, stress, or prolonged forward head posture—this neat coordination goes out the window.

Key muscle players in this system include:

Geniohyoid: Connects the inside of the chin (mandible) to the hyoid. When activated, it pulls the hyoid forward and slightly upward—essential for airway patency.

Mylohyoid: Forms the floor of the mouth, providing muscular support for the tongue.

Digastric: A two-bellied muscle that acts like a pulley, influencing jaw depression and hyoid elevation.

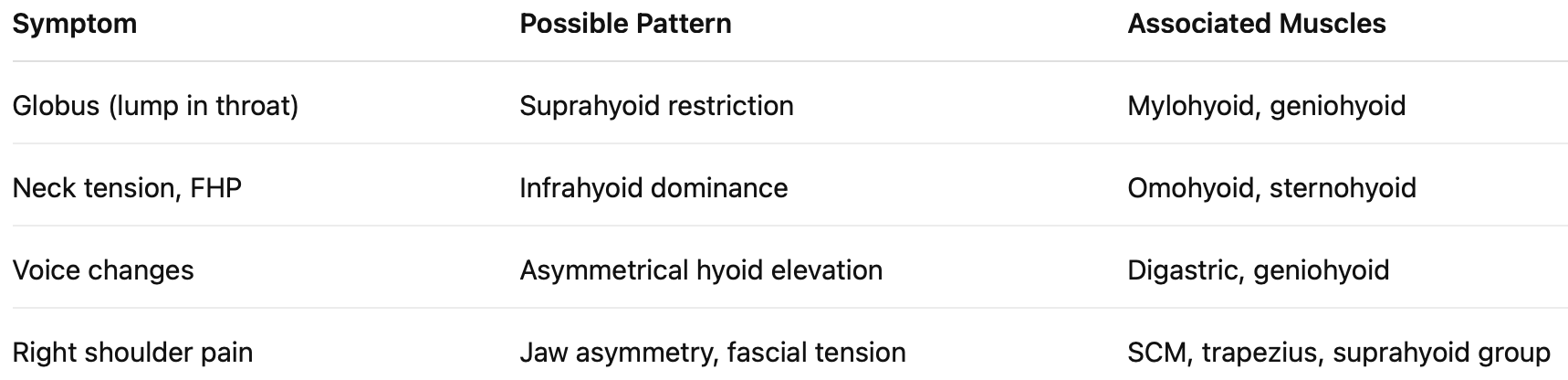

Poor function in these muscles—too tight, too long, or simply not coordinated—can show up as jaw pain, swallowing difficulty, neck strain, or even altered vocal quality (Choi et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023).

Breathing: More Than In and Out

Let’s talk airflow. Functional breathing begins with nasal inhalation, ribcage expansion, and coordination between the diaphragm and accessory muscles (like the scalene group, sternocleidomastoid, and intercostals).

But when hyoid or jaw dysfunction enters the scene, we often see compensatory breathing patterns:

Mouth breathing bypasses the nasal airway, lowering tongue posture and reducing stability of the hyoid bone (Ryu et al., 2018).

Forward head posture causes cervical muscles to overwork, pulling the hyoid inferiorly and straining infrahyoid tissue.

Sleep-disordered breathing (snoring, apnoea) can stem from poor tone in suprahyoid muscles, allowing airway collapse during sleep.

So that gurgle in your throat, the need to constantly clear your voice, or the snore you swore wasn’t you? It may be linked to hyoid muscle dysfunction.

Posture, Fascia, and Functional Tension

Your hyoid doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It’s intricately tied to your posture—especially cervical spine alignment, rib cage position, and shoulder mechanics.

Fascial continuity means that tension in the jaw can manifest in the neck, shoulders, or even the pelvic floor. Yes, really.

Chronic forward head posture creates a downward drag on the hyoid, altering the resting position of your tongue and shifting breathing mechanics (Ishida et al., 2021).

Unilateral jaw tension can lead to right-sided shoulder or neck pain through fascial chains and compensatory patterns (Sato et al., 2021).

When we assess posture at The Body Lab, we don’t just look at whether your chin juts forward. We track how your jaw, cervical spine, rib cage, and even your diaphragm are behaving—and what that means for your ability to breathe, speak, move, and sleep efficiently.

Why Swallowing Matters (And How to Use It in Assessment)

Swallowing is like a live demo of your hyoid’s function in real time. If your hyoid doesn’t elevate, stabilise, or move symmetrically, you’ll feel it.

Try this at home:

Place two fingers on your throat, just above the Adam’s apple.

Swallow normally. Feel that small upward movement?

Now place your tongue firmly on the roof of your mouth and try to swallow again.

Is it harder? More effortful? That may suggest coordination issues between your tongue, jaw, and hyoid.

This simple test is one of several we use in clinical assessment to determine muscle function, restrictions, and neurological control.

When Things Go Wrong – Dysfunction in the Jaw, Hyoid, and Breathing System

Swallowing Struggles and Dysfunction Patterns

Swallowing is a finely-tuned sequence of muscular contractions involving over 30 pairs of muscles, all coordinated in milliseconds. And the MVP of this action? You guessed it—the hyoid.

But when there’s dysfunction, that smooth sequence turns into a clunky, inefficient struggle. People may experience:

A “lump in the throat” sensation (globus pharyngeus)

Clicking or discomfort when swallowing

Habitual coughing or throat clearing

Fatigue when talking for long periods

A delayed swallow or pooling of saliva

Clinically, these are red flags that the suprahyoid or infrahyoid systems aren’t doing their job. For example, if the geniohyoid isn’t functioning, the hyoid won’t move anteriorly or elevate, impairing upper oesophageal opening (Kim et al., 2023). And when muscles like the mylohyoid or stylohyoid are hypertonic (locked short), they can restrict upward motion altogether.

Bruxism, Jaw Tension, and Muscle Imbalance

Now let’s grind into something familiar: bruxism, or jaw clenching/grinding. While often linked to stress or dental alignment, bruxism has deeper muscular and neurological ties:

Overactive masseter and temporalis muscles clamp down

The suprahyoid muscles lengthen under constant tension

Infrahyoid muscles may overwork to stabilise the hyoid inferiorly

Chronic clenching pulls the hyoid backward and downward, reducing airway diameter (Whelan et al., 2017)

Sound like a recipe for sleep-disordered breathing? It is.

In fact, a lot of bruxism is your body unconsciously trying to open your airway—particularly during sleep. Unfortunately, this leads to a vicious cycle of jaw tension, shoulder tightness, poor sleep, and daytime fatigue.

The Posture-Jaw-Breathing Triangle

Let’s connect a few more dots.

Forward Head Posture

Every inch your head moves forward = 4.5–5kg of added strain on neck muscles. This pulls the hyoid down and back, placing a constant stretch on infrahyoid muscles. These are now stabilising under duress, affecting everything from swallowing to phonation.

Rounded Shoulders

A collapsed thoracic posture compresses the ribcage, limiting diaphragm excursion. This shifts breathing upward—recruiting neck and jaw muscles for compensation. Yes, that tight jaw might actually be from your rib cage.

Mouth Breathing

Often a consequence of nasal congestion or poor tongue posture, mouth breathing positions the tongue low in the mouth. This destabilises the hyoid and shifts it posteriorly, which contributes to:

Weak suprahyoid muscles

Loss of tone in the upper airway

Narrowing of the oropharyngeal space

Changes in mandibular development in children (Ryu et al., 2018)

Long-term? You’re looking at chronic fatigue, postural asymmetry, TMJ dysfunction, and even voice changes.

Functional Implications for Speech and Voice

The hyoid doesn’t just make swallowing happen. It plays a huge role in voice production and projection.

Suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles control pitch, volume, and tone through:

Stabilisation of the larynx (voice box)

Modulation of vocal cord tension

Coordination of tongue-jaw-hyoid timing

People with hyoid dysfunction often report:

A “tight throat” when speaking

Voice fatigue after meetings or teaching

Inability to project voice loudly

Flat or monotone vocal tone

If you’re a singer, teacher, therapist, or human being who occasionally talks—this is relevant to you.

How We Assess This at The Body Lab

We don’t just treat symptoms—we trace patterns. Here’s a breakdown of how we assess hyoid and jaw function in practice:

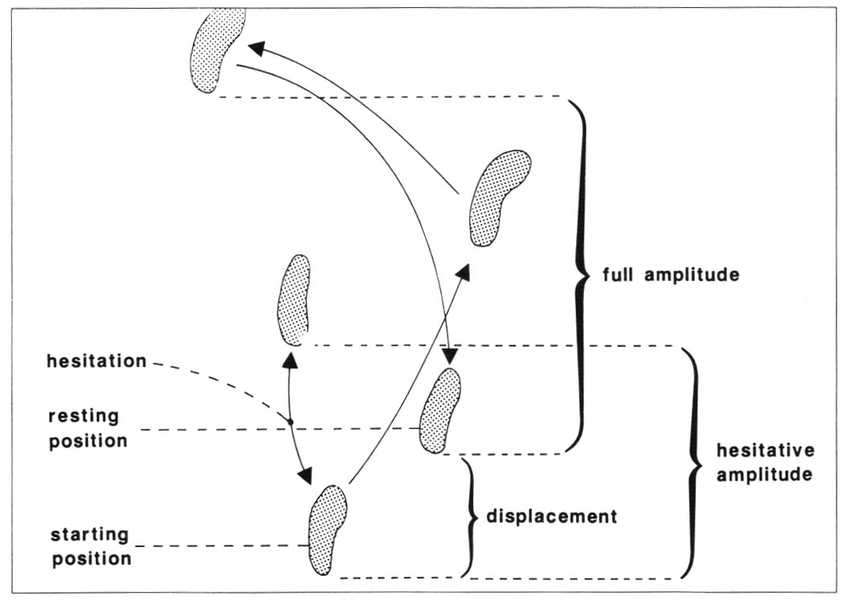

Swallow Test

We palpate the hyoid during a normal and resisted swallow

We note movement amplitude, timing, and direction

Resistance or deviation? You’ll feel it immediately

Tongue-to-Roof Test

The client holds their tongue to the roof of their mouth and swallows

Difficulty indicates poor synchronisation of jaw, hyoid, and tongue musculature

Manual Palpation

We assess tone and tenderness above (suprahyoid) and below (infrahyoid) the hyoid

Unilateral tightness often correlates with shoulder or head rotation issues

Postural Assessment

We observe standing and walking posture

We note head, shoulder, and jaw asymmetries that may impact upper airway function

Breath Pattern Testing

We assess diaphragm function, rib mobility, and accessory muscle recruitment

Mouth breathers, we’re looking at you

This comprehensive approach means we can accurately identify whether you’re dealing with a local dysfunction (e.g., digastric tension) or a systemic coordination issue (e.g., hyoid + tongue + rib cage).

What Happens if We Ignore It?

Here’s the thing: a dysfunctional hyoid rarely stays isolated. Over time, it may cascade into:

Chronic tension headaches

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJD)

Neck and shoulder pain

Sleep apnoea

Vocal changes

Postural asymmetries

Even pelvic dysfunction via fascial lines

It’s not dramatic—it’s just anatomy. When one part of the system goes offline, something else has to compensate. That’s why our model isn’t just “treat the jaw” or “strengthen the neck”—it’s see the whole system.

Clinical Applications and Treatment Strategies

Introduction to Functional Intervention

Treating hyoid and jaw dysfunction requires a blend of biomechanical understanding and clinical finesse. Unlike a sprained ankle, you can’t exactly slap a brace on someone’s geniohyoid. The complexity of this region—functioning at the intersection of swallowing, speech, breathing, and postural control—demands a holistic, movement-integrated approach that recognises how each subsystem influences the next.

This section outlines evidence-based strategies that practitioners can integrate into clinical practice, from manual therapy techniques to movement retraining and breathwork. Each method not only targets local dysfunction but also addresses upstream and downstream implications.

Manual Therapy for the Hyoid and Jaw

Palpation and Safety Considerations

The hyoid bone floats without direct articulation to other bones, making it both fascinating and finicky. Its proximity to the carotid sheath and larynx demands gentle, deliberate handling. Before any intervention, accurate palpation and patient education are key (Whelan et al., 2017).

Use the swallow test or light humming to locate movement of the hyoid. Restricted superior or anterior motion often indicates tension in the suprahyoid muscles, while inferior or posterior restrictions can reflect infrahyoid dysfunction (Kim et al., 2023).

Pin-and-Stretch Techniques

Once restriction is confirmed, apply pin-and-stretch manually:

For suprahyoid dysfunction: Anchor the soft tissue just superior to the hyoid, have the client elevate the tongue to the roof of the mouth, and perform a gentle swallow. This restores upward mobility of the hyoid and improves mandible depression.

For infrahyoid restriction: Pin below the hyoid, cue the client to tilt their head backward while depressing the shoulder, and swallow. This encourages downward and posterior glide (Lee et al., 2019).

Be cautious—too much pressure can irritate the larynx, and no one wants to explain that the treatment plan accidentally became a choking hazard.

Movement-Based Interventions

As we say at The Body Lab: if it moves, it matters.

Tongue-Jaw-Hyoid Coordination

The tongue plays a central role in hyoid dynamics. Asking clients to place the tip of their tongue on the roof of the mouth, behind the upper front teeth (Nasal Tip Contact), and then perform nasal breathing or swallowing helps assess and retrain muscular coordination between the tongue, suprahyoids, and mandible.

This cueing improves the function of:

Genioglossus and geniohyoid (tongue–jaw–hyoid linkage)

Mylohyoid and digastric during swallowing

Mandibular depression and elevation timing

Clients often report improved swallowing, reduced tension under the jaw, and less shoulder discomfort after consistent practice.

Breathing and Postural Re-Education

Because the hyoid is a biomechanical bridge between the jaw and the thorax, breathing plays a pivotal role in functional integration.

Straw Breathing & Diaphragmatic Training

Using straw breathing—especially through smaller diameters—prolongs exhalation and increases vagal tone (Ishida et al., 2021). This is useful when the nervous system is stuck in “survival mode” or if oral compensation dominates respiration.

Technique:

Inhale through the nose

Exhale through a small straw

Focus on keeping the tongue on the palate

Combine with hyoid palpation and note changes

This technique not only aids respiratory control but restores the rhythmic dance of the suprahyoid group during each breath.

Postural Reintegration

Forward head posture and scapular protraction often accompany hyoid dysfunction (Sato et al., 2021). Functional corrections should target:

Scapular positioning: Retraction with gentle loading

Thoracic mobility: Rotation and extension drills

Cervical stacking: Cues like “grow tall through the crown”

These indirectly decompress the hyoid-jaw space, reducing compensatory tension and improving mechanical efficiency.

Regional Interdependence and Chain Reactions

A dysfunctional hyoid doesn’t just stop at the neck.

Shoulder pain may originate from persistent suprahyoid tightness affecting clavicular mechanics.

Low back pain may be exacerbated by compensatory breathing strategies and cranio-cervical misalignment.

Voice fatigue can result from inefficient hyoid elevation and tongue compensation, affecting pharyngeal tone.

By addressing these through local (manual therapy), regional (posture), and global (breathing/movement) lenses, practitioners can unlock more durable outcomes.

Functional Progressions and Home Exercises

Self-Palpation and Biofeedback: Clients can be taught to feel their own hyoid during light humming, tongue presses, and swallowing tasks.

Mirror-Based Tongue Training:

Tongue-to-palate holds (30 seconds)

Swallowing with tongue elevated

Combine with nasal breathing

Wall Posture and Chin Nod:

Back to wall, feet hip-width

Nod chin down slightly while maintaining neutral spine

Focus on hyoid lift during swallowing or humming

These are simple, repeatable, and empowering for clients—bridging the clinical gains with long-term behavioural change.

The Hyoid as a Central Regulator of Systemic Function

The hyoid bone, often ignored in clinical assessments, plays a pivotal role in regulating multiple systems—respiratory, masticatory, vocal, and postural. As a “floating” bone, it acts as an anatomical and neurological bridge between:

Oral motor function (speech, swallowing)

Airway stability (nasal vs. mouth breathing)

Cervical spine alignment

Scapular and shoulder mechanics

Cranial and fascial tension systems

When this central regulator is off-kilter, it can produce a cascade of compensation patterns—what’s often treated as isolated neck, jaw, or even shoulder pain may have roots in hyoid or tongue dysfunction (Ishida et al., 2021; Yoo et al., 2020).

Interdisciplinary Implications

Let’s dive into how this knowledge applies across fields.

Dentistry and Orofacial Myology

Dentists often see patients with malocclusion, tongue thrust, or temporomandibular dysfunction. These conditions frequently involve altered suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscle function. Inappropriate tongue posture, open-mouth breathing, or poor swallowing mechanics directly affect mandibular alignment and bite force distribution (Park et al., 2015).

Interventions like myofunctional therapy (MFT) that incorporate tongue-palate exercises, nasal breathing retraining, and hyoid mobility drills can improve orthodontic outcomes and reduce relapse (Choi et al., 2022).

Key Crossover: Collaborative work between dentists and manual therapists can enhance tongue-hyoid coordination and jaw stability.

Speech Pathology

Speech and swallowing disorders (e.g., dysphagia, dysarthria) are strongly influenced by hyoid kinematics. Restricted hyoid elevation or infrahyoid overactivity can impede bolus propulsion or vocal fold control (Kim et al., 2023; Ryu et al., 2018).

Speech pathologists benefit from referring clients for manual therapy to reduce myofascial restrictions, improve hyoid motion, and retrain breath-voice coordination. Biofeedback tools (e.g. surface EMG) can also track improvements in suprahyoid muscle activation.

Key Crossover: A combined approach of structural release + functional cueing can significantly enhance speech and swallowing outcomes.

Physiotherapy and Osteopathy

Postural dysfunction is a classic presentation in physiotherapy clinics. Forward head posture, thoracic collapse, and scapular winging often stem from dysfunctional upper airway and tongue mechanics (Sato et al., 2021).

The hyoid’s muscular attachments influence:

C1–C3 vertebrae (via longus colli and suprahyoids)

Sternum and clavicle (via sternohyoid, omohyoid)

Mandible (via digastric, geniohyoid)

Restoring hyoid-centred motion improves cervical alignment, reduces thoracic restriction, and enhances global stability (Tanaka et al., 2019). Additionally, fascial chains from the hyoid connect to the diaphragm and pelvic floor, influencing core function (Myers, 2020).

Key Crossover: Incorporating hyoid and jaw mobility into posture and core rehab can resolve longstanding compensatory patterns.

Movement Therapy and Performance Coaching

Breathing and jaw tension are common in athletic populations—from runners with clenched jaws to dancers with tongue-thrust breathing. Dysfunctional breathing patterns (mouth breathing, paradoxical breathing) affect diaphragm-hyoid synchronization and contribute to overuse of accessory muscles like the sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius (Whelan et al., 2017).

Incorporating straw breathing, palate holds, and nasal-only cardio can:

Improve vagal tone (Ishida et al., 2021)

Increase endurance

Reduce tension-related injuries

Key Crossover: Movement therapists and coaches can optimise posture and performance by cueing tongue position, nasal breathing, and jaw relaxation.

The Hyoid and the Nervous System

The hyoid’s neural integration makes it a gateway for autonomic regulation. Fascial connections between the hyoid and cranial base interface with:

Cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, XI, XII

Cervical sympathetic chain

Vagus nerve

Disorders like persistent anxiety, globus sensation, and chronic throat clearing often reflect sympathetic dominance and vagal hypoactivity. Techniques that mobilise the hyoid gently—especially during exhalation—can act as a neural reset for the autonomic nervous system (Ishida et al., 2021).

Clinical Tip: Use vagus-supporting techniques (e.g., hum-and-swallow, head turn + swallow) to reset autonomic tone and improve breath-voice coordination.

Clinical Case Patterns and Observational Clues

Though individual case studies are beyond the scope of this section, we see recurring patterns in clinical practice:

These observational clues can guide clinical reasoning and tailor assessment sequences.

Hyoid Dysfunction in Children

Paediatric clients with ADHD, speech delays, or sensory processing difficulties often display:

Open-mouth posture

Mouth breathing

Poor tongue-palate contact

Slouched thoracic posture

These issues are not just behavioural—they are biomechanical and neurological.

Combining cranial-sacral work, tongue retraining, and breathing therapy supports nervous system regulation and improves orofacial function (Yoo et al., 2020; Ryu et al., 2018).

Interdisciplinary Potential: Collaborative care with occupational therapists, speech therapists, and craniofacial specialists is key for long-term gains.

A Whole-System, Movement-First Model

At The Body Lab, we advocate for a movement-first model—not as an alternative to manual therapy, but as its logical progression.

“Manual therapy + movement = integration. Breathing + tongue + posture = regulation.”

Clients experience longer-lasting change when interventions are reinforced with:

Tongue training drills

Swallow-breath coordination

Dynamic postural retraining

Breath-led movement exercises

This aligns with emerging research showing that suprahyoid muscle training improves cervical mobility, scapular control, and even grip strength (Ishida et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2022).

Conclusion

The hyoid is the unsung hero of the upper body, silently coordinating a vast network of functions—breathing, swallowing, speaking, posturing. Yet dysfunction in this tiny bone and its attached muscles can manifest in widespread, seemingly unrelated symptoms.

Integrating assessment of the tongue, jaw, hyoid, and breathing into clinical practice unlocks deeper insights into chronic conditions, from TMJ issues to posture-induced shoulder pain.

A truly integrated approach—combining palpation, breath work, manual release, and movement retraining—delivers both immediate relief and lasting change.

ReferencesChoi J, et al. (2022). Tongue and jaw coordination in hyoid stability. Journal of Oral Motor Therapy, 48(2), pp.121–128.Ishida K, et al. (2021). Functional implications of hyoid restriction in posture and grip strength. Manual Therapy Science, 36(3), pp.45–52.Kim H, et al. (2023). Suprahyoid muscle activation and swallowing mechanics. Dysphagia Research, 12(1), pp.34–40.Lee Y, et al. (2019). Manual therapy effects on hyoid elevation in swallowing dysfunction. Clinical Anatomy, 32(4), pp.233–241.Myers T. (2020). Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists. Elsevier Health Sciences.Park S, et al. (2015). Role of suprahyoid muscles in mandibular function. Archives of Oral Biology, 60(11), pp.1553–1559.Ryu J, et al. (2018). Airway manipulation and resulting hyoid dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(6), pp.370–377.Sato M, et al. (2021). Shoulder tension linked to orofascial restrictions. Musculoskeletal Medicine, 28(2), pp.112–118.Tanaka T, et al. (2019). Restoring hyoid-mandibular coordination in jaw dysfunction. Manual Therapy Journal, 24(1), pp.91–98.Whelan J, et al. (2017). Assessment of the hyoid complex in myofascial restriction. Physical Therapy Perspectives, 14(3), pp.98–107.Yoo D, et al. (2020). Anatomical review of hyoid-jaw-tongue relationships. Clinical Myology, 19(4), pp.277–283.